- Meet the Casts of the 2008 Season

- Spotlight on The Winter’s Tale

- Spotlight on Amadeus

- Spotlight on Much Ado About Nothing

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

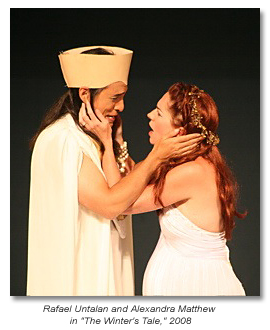

The Winter’s Tale

The Winter’s Tale

The Winter’s Tale was listed in the first Folio as a comedy and it contains much humor, including its most famous stage direction: “Exit, pursued by a bear.” Contemporary scholars group the play with what are known as the “Late Romances.” These plays are considered the last ones written by Shakespeare and include The Winter’s Tale, Pericles, Cymbeline and The Tempest. The Romances are intense psychological dramas with sweeping plots that include wild adventures, great storms, lost princesses and happy endings, and each one ends with forgiveness and a sense of grace. They are lyrical, mystical stories of the recognition of human frailty coupled with a belief in ultimate hopefulness.

Like The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale can be imaginatively read as a highly personal, autobiographical play. A powerful man succumbs to a jealous rage which destroys his marriage, alienates his daughter, and finally brings him to acknowledge his own weakness. It is easy to imagine that rage over real or perceived adultery was an issue in Shakespeare’s long-distance marriage to Anne, who was left alone in Stratford for long stretches of time while her husband worked in London, several days’ journey away at that time. It is easy to imagine the absent father feeling guilt over his relationship with his daughter, who might have seemed lost to him. And it is easy to believe that at the end of his career, Shakespeare was thinking about and hoping for forgiveness for life’s sins, despite feelings of unworthiness – a spiritual re-birth into the Edenic innocence of youth which Polixenes describes in Act I when: “we knew not / The doctrine of ill-doing, nor dreamed / That any did.”

One delightful thing about The Winter’s Tale is Shakespeare’s personification of Time. After decades of writing about time in all its guises, Shakespeare finally creates a character named Time who appears in this play. Of all the themes Shakespeare returns to throughout his writing, Time is his greatest motif – his biggest mystery, consolation and constant mental companion

Amadeus

Mozart (1756 – 1791) was a prolific writer of over 600 musical compositions including symphonies, operas and choral music. He began composing at age 5 and performing publicly as a child. Raised by his father Leopold, a court musician, composer and music teacher, Mozart had a natural facility for music and travelled widely throughout Europe, meeting many leading musicians of his day. Yet Mozart had many setbacks. His mother died when he was only 22 years old. He struggled to win his father’s approval. His first job in Salzburg ended when he quarreled with the Archbishop whose steward eventually dismissed him with a literal “kick in the arse.” While early success in Vienna brought him wealth and acclaim, he never succeeded in obtaining a full-time job as a court musician and ran into financial difficulties that left him begging his friends for cash. His music, though now regarded as some of the most sublime ever composed, was not always understood and appreciated by his contemporaries. His early death at age 35 followed a life marked by illnesses like smallpox and perhaps depression.

Meanwhile, lesser musicians like Antonio Salieri thrived professionally, succeeded financially, and were well respected by society.

Out of what is known about these lives, Peter Shaffer has fashioned a brilliant play that has been a Broadway hit and a major motion picture. Viennese court musician Antonio Saleri sells his soul to achieve his ambitions as a composer and achieves great public success. Yet the immature, sexually scandalous, fun-loving Mozart seems effortlessly to create works of music of indelible beauty. He is, after all, “Amadeus,” beloved of God. Salieri takes the audience along a journey into the innermost blackness of his heart as he foils Mozart’s ambitions and ultimately helps drive the young genius into an early grave. Written in the style of noir thriller, the play uses words and music to unfold this stunning mystery of envy and glory.

Much Ado About Nothing

Often, we are asked how we choose plays for each summer’s season. Sometimes, we are drawn to discover the joys of a rarely performed play, or one we have never explored before, like The Winter’s Tale. Sometimes, we are compelled to choose a piece like Amadeus that we’ve talked about producing for many years. Yet sometimes, we choose plays for specific artists — a director who has a burning desire or a striking concept for a particular play or, more often, an actor who we think will be brilliant in a particular role at this very moment in their career.

Our 2008 production of Much Ado falls into this last category. Not one, but two, of our favorite actors came to us and pitched us on this play as a vehicle for their comic talents. When the incredibly sexy and wacky Cat Thompson and the endearingly charming and comic Darren Bridgett want to spar romantically onstage in one of the bard’s most delightful comedies, it would be foolish to resist.

Much Ado continues the season’s exploration of jealousy – a theme Shakespeare returned to often in his plays. From Leontes’ irrational jealousy to Salieri’s covetous envy to Claudio’s naively boyish resentments, we explore the green-eyed monster in all its tortured incarnations. Of course, there is a happy ending.